Do You Have to Be Toxic to Get to the Top

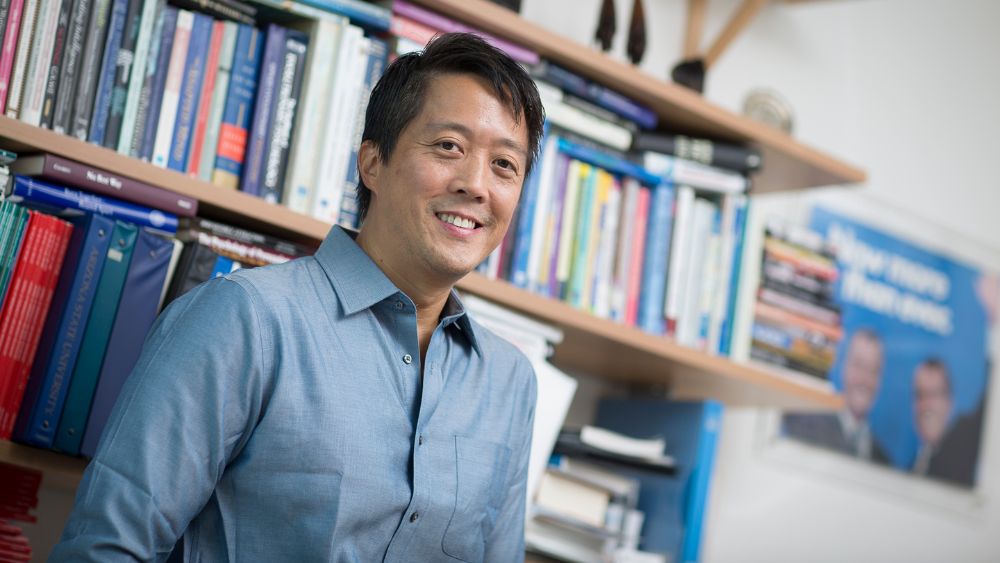

A study on psychopathic traits in business leaders found that 20 per cent of CEOs are psychopaths. Norman Li, Associate Professor of Psychology at the SMU School of Social Sciences, explains why CEOs and big bosses tend to have more of these traits than people who are not or do not wish to be big leaders.

The Dark Triad may sound like a conglomerate of villains in some fictional fantasy universe, but unfortunately, it is all too real. It’s actually a psychology term for the lethal combination of three traits: psychopathy (low empathy and concern for others), narcissism (being especially self-interested) and Machiavellianism (being manipulative).

Even if one is lucky enough to have never worked with people who possess the Dark Triad, it’s not too difficult to find evidence of such individuals just by scanning the daily headlines. For every self-aggrandising leader whose toxic behaviour leads to their downfall (see Uber’s Travis Kalanick and WeWork’s Adam Neumann), there are more who continue to run amok (see outgoing US President Donald Trump, who—according to one study from Oxford University—has more psychopathic traits than Adolf Hitler).

Psychopath for a CEO

Indeed, a study on psychopathic traits in business leaders by forensic psychologist Nathan Brooks showed that 20 per cent of CEOs are psychopaths (about the same ratio found in prisoners, and much higher than the 1 per cent rate among the general population). Its findings seem to confirm anecdotal evidence that it’s easier for psychos to get to the top.

But is this really true? Norman Li, Associate Professor of Psychology at the SMU School of Social Sciences, does believe that while everyone has varying degrees of the Dark Triad, “CEOs and big bosses tend to have more of these traits than people who are not or do not wish to be big leaders”.

“As with most behaviours, the Dark Triad stems from a combination of biological (genetic) predispositions and environmental influences. People with these traits, for example, tend to have had traumatic experiences during childhood,” he elaborates. “Together, these traits may facilitate people’s success in competitive environments because they allow people to focus on getting themselves promoted and utilising others to their advantage without feeling bad about doing so.”

Other factors, however, may complicate the overall picture. For starters, a 2018 study showed that earlier claims of a high proportion of psychopathic personalities among CEOs may be overblown. Its findings were more nuanced: the researchers found that individuals with psychopathic tendencies were slightly more likely to become leaders, but less likely to be seen as effective leaders. Furthermore, men with psychopathic tendencies were more likely to become leaders and were rated as more effective leaders than women who displayed the same tendencies.

Men with psychopathic tendencies were more likely to become leaders and were rated as more effective leaders than women who displayed the same tendencies.

Associate Professor Li sees this latter finding as evidence of a double standard. “Women who act assertively and display status and power tend to be disliked by both men and other women. So there are likely more limits on the effectiveness of Dark Triad strategies when they are enacted by women. I suppose that women may have to be more subtle and indirect at times than men.”

Gender

To view this issue through the lens of gender is not to assert that an equal playing field is missing among the genders even in behaving badly (although that has a perverse ring of truth). Rather, as leadership ranks grow more diverse, a better awareness of a wider range of potentially problematic behaviour can be a more useful warning system. WeWork’s Rebekah Neumann, for instance, ran the business with an intense focus on appearances over substance, while the female founders of co-working space The Wing have been criticised for branding their endeavour with progressive buzzwords that are not always backed up by equitable workplace policies. Elizabeth Holmes, the disgraced founder of blood-testing start-up Theranos, has been described as having sociopathic tendencies, including pathological lying. Less familiar than the aggressive bullying tactics of toxic male CEOs, such female leadership patterns can nevertheless have similarly dismal consequences for employees and society at large.

Less familiar than the aggressive bullying tactics of toxic male CEOs, such female leadership patterns can nevertheless have similarly dismal consequences for employees and society at large.

A rigged game

And those consequences are the real crux of the matter. After all, one of the major reasons toxic CEOs are the subject of so much interest is because there is an increasingly pervasive sense that the corporate sector is a rigged game, plagued by income inequality, corruption, and hyper-focused on the bottomline, above all else.

In that sense, toxic CEOs are a symptom of a system that they then help to perpetuate. “Such a system may indeed encourage such behaviours, because without other KPIs or rules in place, people who want to get ahead and rise to the top will have to beat out others on the bottomline,” says Associate Professor Li. “This is especially true when assessments depend on short-term bottomlines like quarterly results, because unscrupulous strategies and behaviours are often discovered over time. In the long run, various costs and inefficiencies will likely accrue as resources that could have been optimally used by the organisation, or more fairly distributed to its employees, will be channelled to high-ranking Dark Triad individuals and their agendas. It is also likely that employees will incur psychological costs working under such individuals, thereby leading to greater turnover.”

“Employees will incur psychological costs working under such individuals, thereby leading to greater turnover.”

Norman Li

Associate Professor of Psychology at SMU School of Social Sciences

How can companies root out such toxicity? Associate Professor Li believes structural changes are needed. “Organisations can reward longer-term objectives and cooperative over individual effort, select and screen CEOs based on psychological assessment, slow down the decision-making horizon, implement checks and balances including oversight by an independently-formed board of directors, and place requirements for transparency to limit the power and control of any one individual.”

Keen to explore your interest in psychology with SMU? Check out our Bachelor of Social Science programme today.